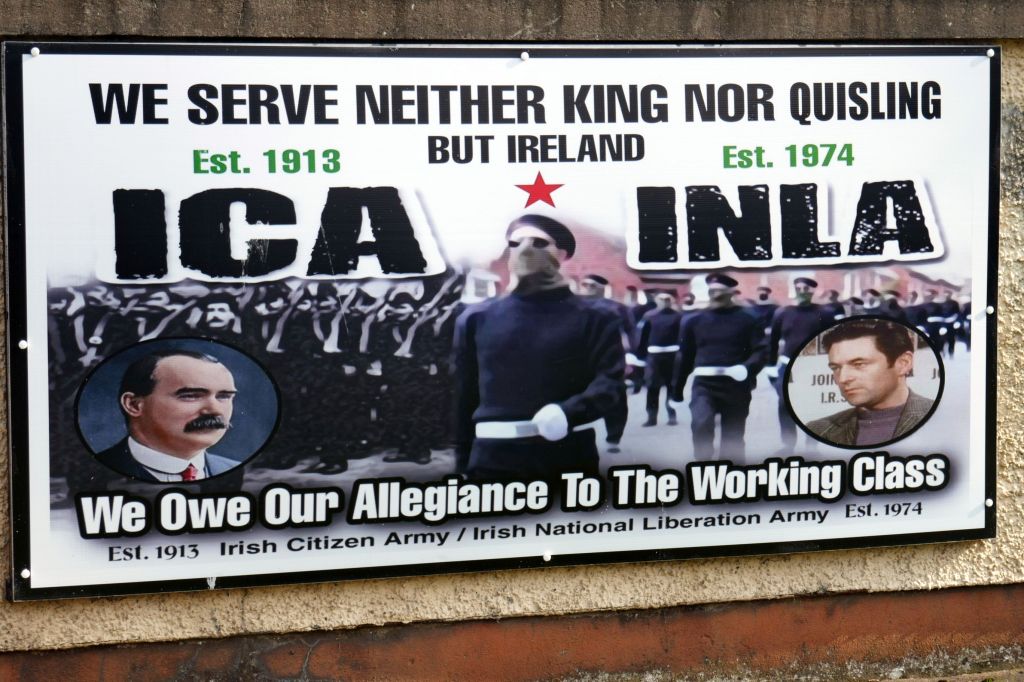

In a previous post, IRISH ADVENTURE #6: THE TROUBLES OF THE 1970s: THE SITES AND STORIES, I wrote about our experience hearing about his significant time in Ireland’s history from the perspective of our taxi tour guide as well as a panel of three men, in Belfast.

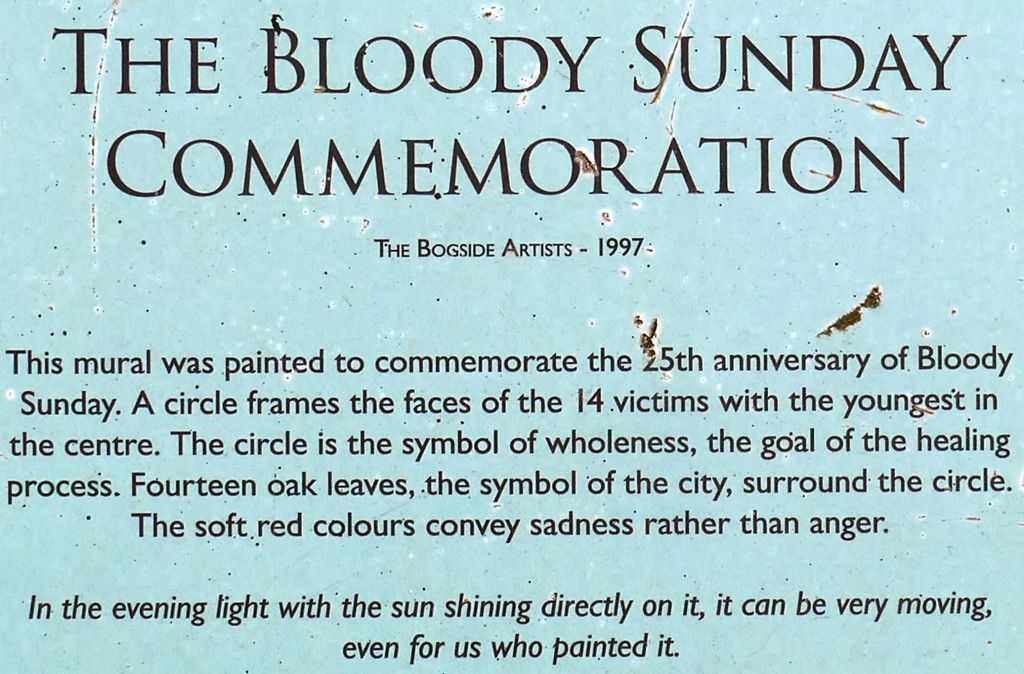

This post is about the 1972 Bloody Sunday Massacre that occurred in Derry, Ireland, 70 miles from Belfast, in Northern Ireland. We visited the Museum of Free Derry and listened to the experiences of an Irish Catholic who witnessed it that day.

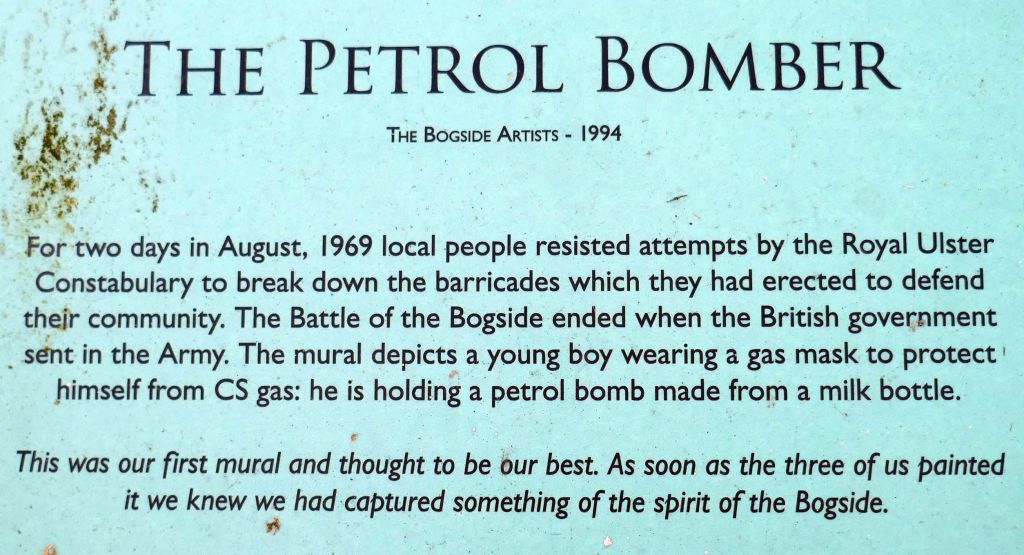

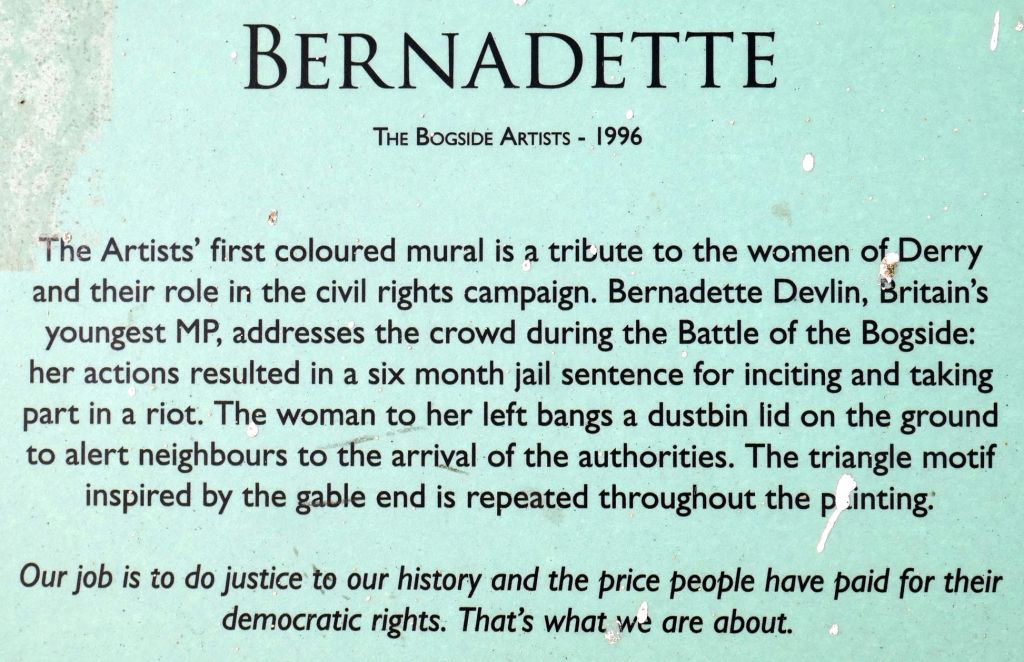

The Museum of Derry documents the history and events of the struggle of the Irish Catholics, as do the murals I photographed along the streets surrounding the museum. Powerful, thought-provoking, and all too familiar, considering what transpired during the same time in the U.S.A.

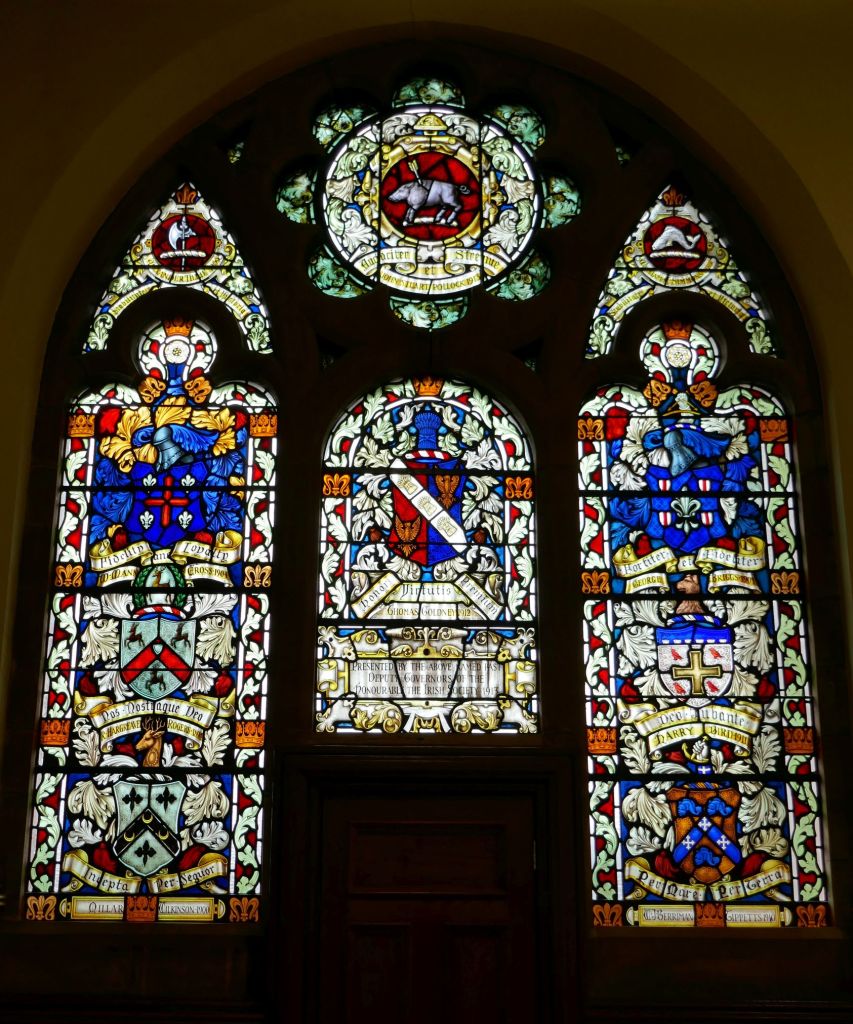

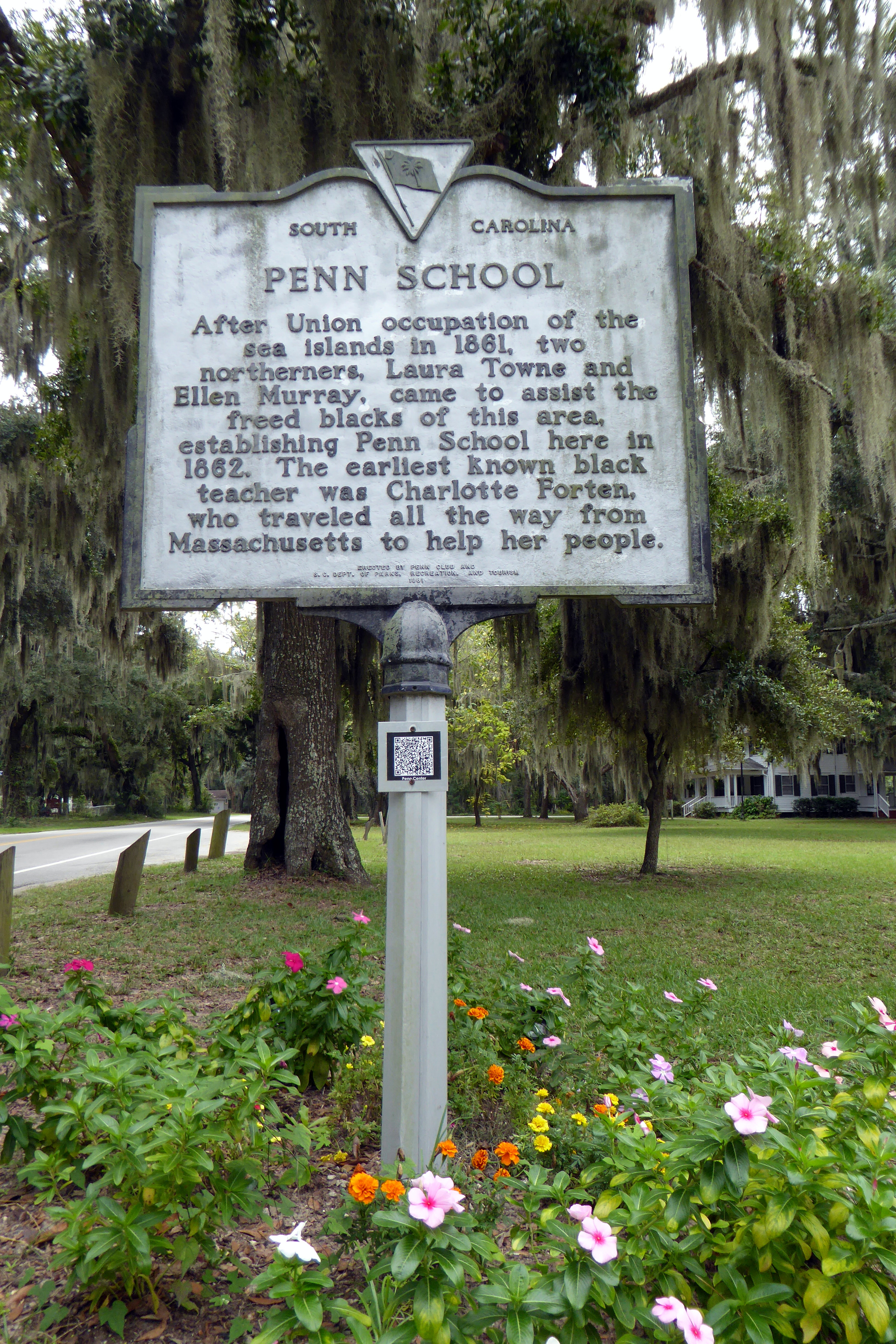

Derry (previously called “Londonderry” by the British from London who had settled there), is 85% Irish and is seen as an Irish city, even though it is part of Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom. Although it should have been part of the Republic of Ireland, the British maintained a hold on the city through gerrymandering. As a result, the Irish Catholics had to stand up to the British for their civil rights, including equal pay for equal work, equal right to jobs without discrimination, and the right to vote without being a landowner. They modeled their movement after the United States civil rights movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and marchers would sing, “We Shall Overcome.”

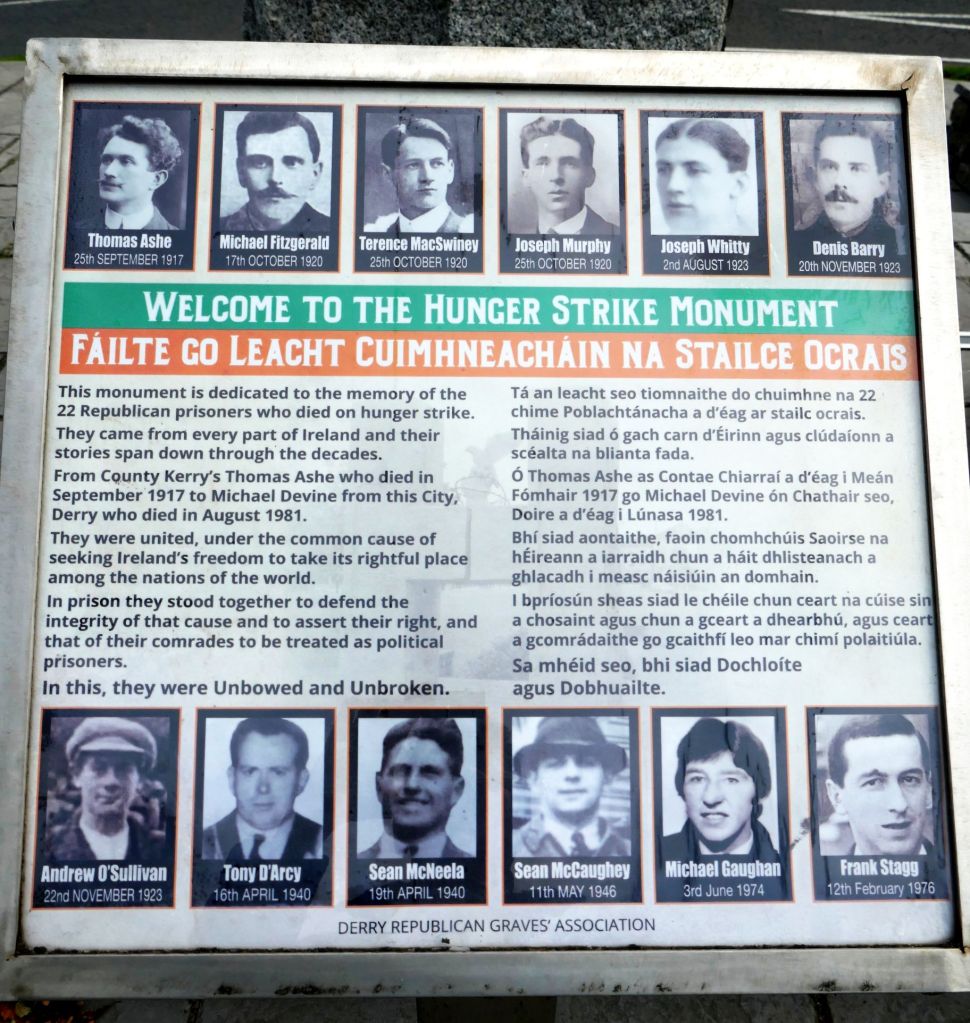

In 1969, Protestant loyalists marched into the Bogside district, a marsh land outside the walls of Derry, sparking violence with the Catholic residents. Formerly known as the Battle of the Bogside, this attack would become the starting point of The Troubles, and the Irish civil rights movement for equality that culminated in the 1972, Bloody Sunday Massacre. The massacre occurred when 15,000 protesters took to the streets in the Catholic Bogside neighborhood of Derry to march against an internment law granting the British government the authority to imprison Northern Irish dissidents without a trial. The crown deployed soldiers to police the march, and after a day of escalating violence, the army fired upon the unarmed crowd, shooting 108 live rounds that left 14 dead and many more injured. To make matters worse, an official British inquiry cleared the soldiers who murdered these unarmed protesters. All the British officials had to say about what happened was that the soldiers’ behavior was “bordering on the reckless.” Despicable.

Only one British soldier was ever charged with a crime for the 14 Irish Catholics who were murdered during the 20-minute period of Bloody Sunday. To this day, there are Derry residents, including those who started and run the museum, who continue to fight for those who lost their lives on that day (and throughout the Irish civil rights movement)—especially the children who were murdered while just trying to get to safety during the violence.

(For all photos, click on the image for a full screen view.)

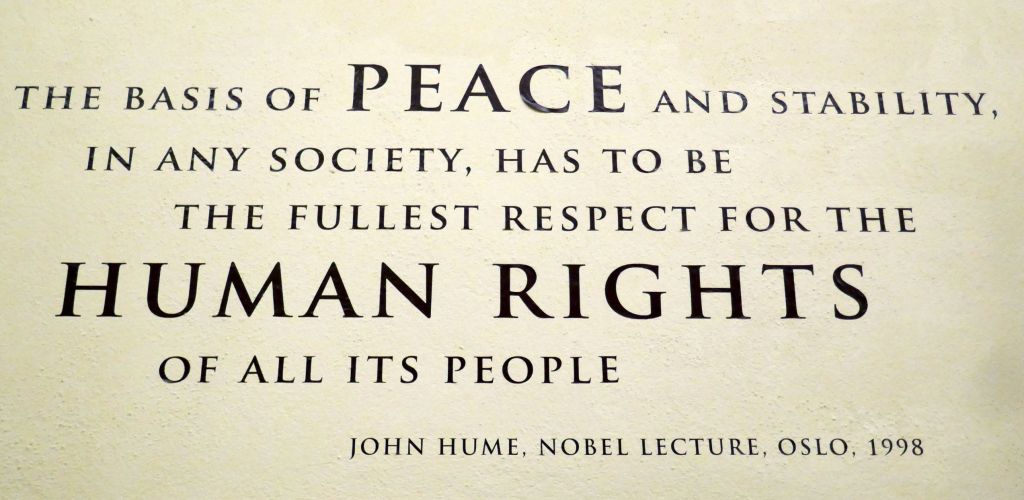

It wasn’t safe for Irish Catholics to walk the streets until 1998 when the British army finally moved out of Derry. Their army barracks were located across the river from town, and there is now a bridge, built in 2011, connecting the two sides, called the “Peace Bridge.”

Thankfully, there is full equality now for the Irish Catholics, but following the war, there was a high rate of PTSD, drug addiction, and alcoholism.

Derry is surrounded by stone walls that were built between 1613 and 1619. Following our visit to the museum, we went on a walking tour of the walls with a local guide. He pointed out that the well-off British Protestants lived inside the city walls, and the Catholics lived outside. At 9:00 PM, a bell would ring to alert any Catholics working or visiting inside the city that they had to leave and return to their ghetto. Notice the difference between the neighborhoods outside the walls and inside, in the pictures below. This first shot was taken from on top of the city wall, looking down to where the Bloody Sunday Massacre took place in the Irish Catholic neighborhood, outside of the walls.

Following time on our own to walk the Peace Bridge, we continued our overland to Donegal, Ireland, the subject of my next post: IRISH ADVENTURE #11: A DAY IN DONEGAL